December 2010

27 December 10

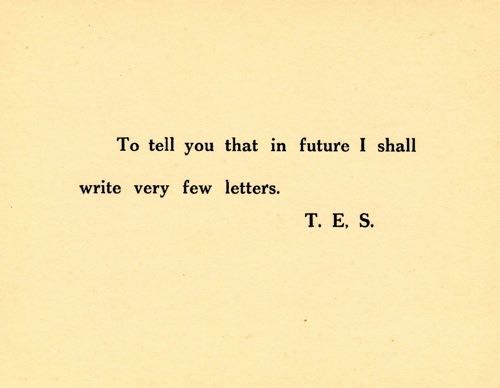

Very Few Letters

— [T. E. Lawrence]. To tell you that in future I shall write very few letters. T. E. S. Printed card, [February 1935], sent by Lawrence to his correspondents in early 1935. O’Brien A161. An uncommon piece of ephemera.

Effective with this post the Endless Bookshelf will adopt a new, monthly schedule for updates. The next sections of the Endless Bookshelf will appear on 27 January 2011.

Marginal notes about current and recent reading will still continue to appear in the interval. Readers are especially encouraged to send lists of The Last Three (books read), which now cumulates here. (And if you are looking for suggestions for reading, The Last Three is as eclectic and erudite as any list you will find.)

Your correspondent has a few writing assignments to complete over the next several months that will reduce the amount of time available to produce the Endless Bookshelf.

Thank you for your regular attention to these columns over the past four years. Please walk through the archives and continue to send comments and suggestions. Happy new year ! [HWW]

‘ tell the truth ’ : James Connolly in Ireland and America

“ ‘ Let us free Ireland, ’ says the patriot who won’t touch Socialism. Let us all join together and cr-r-rush the br-r-rutal Saxon. Let us all join together, says he, all classes and creeds. And, says the town worker, after we have crushed the Saxon and freed Ireland, what will we do ? Oh, then you can go back to your slums, same as before. Whoop it up for liberty ! ” — Let Us Free Ireland ! (1899)

“ We are out for Ireland for the Irish. But who are the Irish ? Not the rack-renting, slum-owning landlord ; not the sweating, profit-grinding capitalist ; not the sleek and oily lawyer ; not the prostitute pressman — the hired liars of the enemy. Not these are the Irish upon whom the future depends. [. . .] Labour seeks to make the free Irish nation the guardian of the interests of the people of Ireland, and to secure that end would vest in the free Irish nation all property rights as against the claims of the individual, with the end in view that the individual may be enrched by the nation, and not by the spoiling of his fellows. ” — The Irish Flag (1916)

Of what use to such sufferers can be the re-establishment of any form of Irish State if it does not embody the emancipation of womanhood. — The Re-Conquest of Ireland (1915)

James Connolly (1868-1916) — socialist, Irish revolutionary, and a martyr of the repression of the Easter Rising — wrote eloquently and prolifically in the decades leading up to 1916, on both sides of the Atlantic (he spent seven years in America working for socialist causes). His vision, Irish and internationalist, is especially clear in his discussion of German socialist and pacifist Karl Liebeknecht, who was executed for refusal of military service in 1914 :

Now we are hearing a new excuse for the complicity of socialists in this war. It is that this war will be the last war, its horrors will be so great that humanity will refuse to allow another. The homely Irish proverb has it that “ far off cows have long horns ”, or that “ far away hills are always green ”. It must have been in some such spirit that this latest argument was evolved. For what cna happen in the future that is not more applicable now ! [. . .] No ; we cannot draw upon the future for a draft to pay our present duties. There is no moratorium to postpone the debt the socialists owe to the cause ; it can only be paid now. [. . .] the war of nation against nation in the interest of royal freebooters and cosmopolitan thieves is a thing accursed.

If Pearse was the dreamer and poet of the Irish rising, Connolly was the practical firebrand and the organizer and orator. He was “a thinker of depth, breadth, and originality, and an orator of force and passion. [. . .] His influence was evident in the egalitarian wording of the proclamation declaring an Irish republic published on Easter Monday 1916 ” (ODNB). He was the one the British were after, says [PD], who has lent me two current reprints of works by him.

— James Connolly. The Re-Conquest of Ireland [Irish

Transport & General Workers Union, 1915 ; NuVision Publications,

2007]. 80 pp.

— James Connolly. Socialism and the Irih Rebellion. Writings Red

and

Black Publishers, [2008 ?]. 263 pp.

Neither of these books includes much in the way of editorial or historical context (I would have liked to learn a little more about the essays and speeches than simply the year in which they were published). The British captured Connolly at the Central Post Office and executed him, but his words remain compelling and timely.

“ Let our readers encourage and actively spread every paper, circular, leaflet or manifesto which in these dark days dares to tell the truth.

“ Thus our honour may be saved ; thus the world may learn that the Home Rule press is but a sewer-pipe for the pouring of English filth upon the shores of Ireland. ” — The Friend of Small Nationalities, September 1914

The Last Three

[MSL] (a partial submission, two titles, but sufficiently interesting to demand inclusion) :

— Edna Ferber. Buttered Side Down (1912)

— Edna Ferber. Fanny Herself (1917)

“ These must

be among the most clothes-focused works of fiction ever penned ;

a pity that the writing itself is mundane at best, and often awful. ” [In

conversation, this reader told your correspondent, I am probably the

only person in the last 50 years to have read these books.]

Recent reading :

“ Reason is not the goddess of emergencies ”

— Elinor Wylie. The Venetian Glass Nephew (1925 ; in Collected Prose , Alfred A. Knopf, 1934). This is an amazing novel, concise, superb in its visual energy ; and to cast Casanova as elderly sorceror is to take an unusual view of historical characters. There are many wonderful passages, such as this one :

The room was called the study , after an English fashion ; its air was warm and intimate. Everyone, with the exception of Virginio, preferred it to the pale and mirrored salon where he now sat alone, nibbling a long green strip of angelica and idly perusing the pages of Frederick Martens’ “ Natural History of Spitzbergen ”. “ There grows an Arctic flower, ” he read ; but his tranqulity was now and again shattered by the heat and hurry of voices from the open door.

Wylie is decidedly ambiguous and indirect in her narration of the final events, but there is no doubt that something monstrous occurred in the “ diabolical ordeal ” in the workshop in Sèvres to reduce the wild and intellectual young woman Rosalba to silence, and to transform her pulsing life into “ a flower flexible, but unmoved by wind. Peter Innocent knew instinctively that her spirit was unstirred by any pang that may not be suffered by an exemplary child of seven. ”

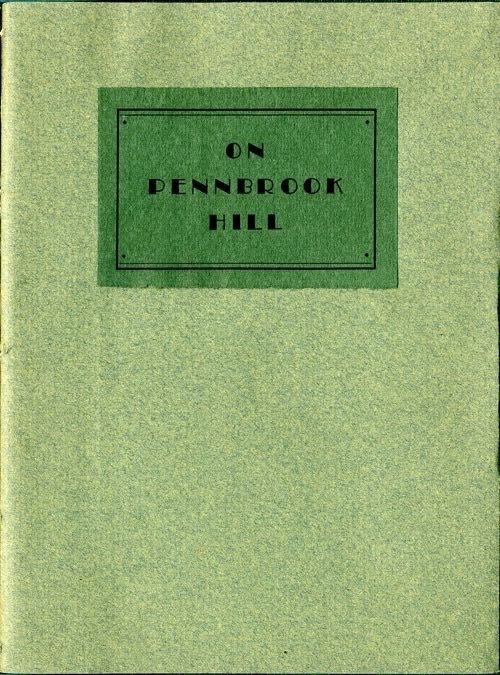

‘ On Pennbrook Hill ’ : a unique printed book

— (New Jersey) [Clarence Blair Mitchell ?] On Pennbrook Hill. Illustrated with six mounted plates from photographs and two line drawings. Unpaginated, [20] pp. [N.p., n.d. (1933)]. Green cloth titled in gilt, preserving sage green wrappers with printed title label on upper cover. Anonymous poem on the Pennbrook mansion (built ca. 1903), local history, and the family, in 24 five-line stanzas (rhymed quatrains aabb, with a refrain of variations of “ On Pennbrook Hill ” : near, from, etc.), presumably printed for family distribution : this copy has an inscription “ To L. M. M. from C. B. M. Christmas 1933 ”, from which one can deduce the author, Clarence Blair Mitchell, who has given the poem to his wife, Lucy Mildred Mitchell (née Matthews).

Clarence Blair Mitchell was a grandson of railroad magnate John Insley Blair, Princeton class of 1889, Columbia Law School class of 1891. He prepared a few other books, including The “ A B C ” of Riding to Hounds (privately printed by the Princeton University Press, 1916) ; a volume of letters from his son Clarence V.S. Mitchell, Princeton class of 1913, With a Military Ambulance in France, 1914-1915 (privately printed, 1915) ; and a genealogical volume, Mitchell Record (privately printed for the use of the family at the Princeton University Press, 1926). Given the family Princeton connection, it might be that On Pennbrook Hill was also printed by the press.

A unique book. Unrecorded in OCLC and the online listings of Rutgers New Jersey Collection or the Jersey Cat.

I have only seen a few unique books in my travels (the Shelley Poetical Essay , 1811, is the most significant recently discovered unique book that I have seen) ; I find it hard to believe no other copy of On Pennbrook Hill has survived, and so will do a little more digging. I have only posted an image of the cover ; and as a matter of interest, an internet search this morning yields no match whatsoever for these words.

24 December 10

The Magic of Class ; or, Will I ever be as rich as my grandfather ?

I first began to reflect on the Magic of Class after discussions with Tom La Farge, who first articulated the term. It was in connection with Little, Big , for one of the voyages of Smoky Barnable in that novel is from being a raw interloper raised in a state beginning with the letter I to embodying the central motive force of Edgewood and the universe. This brief essay takes up some of the threads of “ Appraisal at Edgewood ” (2000) to examine other works of fantastical literature and to limn some of the key landmarks of the Magic of Class (hereafter I shall no longer employ capital letters to accentuate this term, nor privilege other terms except through the transparent magic of context).

In the literature of the fantastic as in the world, the magic of class is a practice that is all the more seductive and powerful (and fascinating) for being almost entirely unspoken ; that is to say, it is a practice of mystification with two aims : to create a language of clues that identify and empower an elite, and to segregate that elite from the population among which (and over which) they exercise their powers.

Every exercise of power incorporates a faint, almost imperceptible, element of contempt for those over whom the power is exercised.

— Sándor Márai, Embers (1942 ; tr. Carol Brown Janeway, 2001)

The magic of class is a subtler exercise of privilege than the raw military and magical powers of Sauron or the wizards of Earthsea, yet not unrelated in its fundamental aims. Distinctions of class are rarely worn like military rank, but they are as immediately made known: consider the second textual appearance of Sam Gamgee in The Fellowship of the Ring : “ But my lad Sam will know more about it. He’s in and out of Bag End. Crazy about stories of the old days he is, and he listens to all Mr. Bilbo’s tales. Mr. Bilbo has learned him his letters — meaning no harm, mark you, and I hope no harm will come of it. ” And while Galadriel seated upon her white palfrey may address him as “ Master Samwise ” at the end of The Return of the King , the truth of the matter is to be found two sentences later : “Sam bowed, but found nothing to say.” And his own use of the word a moment later has an entirely different significance, “ ‘ Where are you going, Master ? ’ cried Sam, though at last he understood what was happening. ”

In America (unlike many other countries and literatures), class is largely confused with money. (Indeed, it was Tom La Farge — not at all confused on this topic — who said in this context that one of the major questions with which to interrogate any work of twentieth-century American literature is, Will I ever be as rich as my grandfather ? The answer to which is almost invariably, No .) In Little, Big the magic of class fundamentally transcends the Drinkwater fortunes, for the American house Edgewood is the soil in which magic brought from England flourishes anew and opens long-standing continuities. And indeed, by the time Smoky’s son Auberon heads to the city, the legacies are starting to run dry but the magical heritage of the family is undiminished.

The Magicians. A Novel (2009) by Lev Grossman is a complex and well written work that engages with the literature of fantasy at the same time as the fantasy central to the novel unfolds. Its opening passages are quite something, both for the way in which the action moves forward, and for the way in which the condensed historiography of Fillory is integral to that headlong displacement. This sentence works, especially the central cadence (italics added) :

The bushes had been trimmed precisely into narrow, branching, fractally ramifying corridors that periodically opened out into small shady alcoves and courtyards.

I also enjoyed the way the way the Fillory novels seemed to be Arthur Ransome recapitulating or anticipating C.S. Lewis, and this aside about Christopher Plover, who “ moved to Cornwall just ahead of the stock market crash. A confirmed bachelor, as the saying goes, he embraced Anglophilia, began pronouncing his name the English way (‘ Pluvver ’), and set himself up as a country squire in a vast home crammed with staff. (Only an American Anglophile could have created a world as definitively English, more English than England, as Fillory.) ” But this essay is not a comprehensive discussion of the textual pleasures of the book, rather a look at key aspects or attitudes it manifests.

For someone who has lived through boarding school and read the stories of Owen Johnson and his ilk, the luster of magic school stories is a little thin. Your correspondent has been immunized, perhaps. In fact this made The Magicians all the more interesting, since I tended to pay more attention to the structure and allusions in the novel than to the school and the illusions. From the very beginning of the book it is clear that the central magic is not the sorcery of Brakebills, but a mystification of class, an enchantment of privilege. As one of the “ nerdiest of the nerds ”, Quentin was already functioning in a quasi-magical environment, and his adaptation is swift. The narrative make it clear that he is an insider, as when he and his western misfit friend Eliot, on Brakebills time, see a West Point eight on the river: “ The occupants looked grim and bundled up against the cold, in gray sweatshirts and sweatpants. They couldn’t perceive, or somehow weren’t part of, the August heat that Quentin and Eliot were enjoying. They were warm and dry and didn’t even known it. The terms of the enchantment locked them out. ”

Quentin’s adjustment to Brakebills was far less difficult than the path described by Walter Kirn in Lost in the Meritocracy (2009): “ In Minnesota I hadn’t had a place, but here I did: several levels down from heiresses who charged their roommates to drink free wine. It seemed unfair that I had come so far in life only to find new ways to fall short. ” Kirn’s taxonomies of his fellow Princetonians as they start to become adults mirror the outward displays of privilege among the Brakebills students. In one memorable passage Kirn is explicit about what is going on :

surrounded by stately trees, an actual castle, with countless tall windows, pediments, and columns. [. . .] “ My family’s estate, ” said Leslie. “ Behold, poor serf ! Behold a power you will never know ! ”

With that he ran back to his car and drove away.

It took me three hours, walking and hitchhiking, to make it back to Princeton.

‘I’ll see what I can do ’

At Brakebills, part of the magic of class involves mastery of languages, which one would think might broaden the outlook, but the narrator and many of his peers are curiously passive about things, and deferential to authority. It is curious how little the sight of his school friend Julia affects Quentin, and how simply he decides to shop her to the headmaster so that her memory of the place, and of the initiatory test which excluded her, will be wiped (pp. 171-5). After graduation, the equation of class with money becomes clear, with huge apartments and slush funds for the young magicians (pp. 227-8), country estates and sinecures. Even the trip to Fillory has them bring along an apparently endless supply of the needed commodities for exchange.

This is of necessity a preliminary step of an essay, but a subject to which I will be returning. I welcome any comments and suggestions.

Your correspondent will embark upon a re-reading of Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast novels, which are an extended satire upon the categories of class : indeed the arc of Titus Groan’s life is to break through the barriers of class. The Endless Bookshelf will update once more before the end of the year. [HWW]

Current reading :

— Elinor Wylie. The Venetian Glass Nephew (1925 ; in Collected Prose , Alfred A. Knopf, 1934). A dizzying, brilliantly crafted novel of an elderly cardinal whose hesitantly voiced wish for a nephew is granted by a murderous Venetian glassmaker and the exiled, almost down-at-heels M. de Chastelneuf, whose title is another, anagrammatic key to his identity : he is the Chevalier de Langeist.* After he speaks an unintelligible syllable, something truly wonderful occurs at the end of the fourth chapter :

Peter Innocent beheld a golden griffin lift his wings to fan the air ; a stag, of azure glass dappled with the same gold, stepped with a fiary pride across the expanse of Chines lacquer which separated him from his mate, and the two, meeting, caressed each other with delicate gestures of affection. A humming-bird, with feathers blown in pearl-colour and crimson, flew from his perch, alighting on the leafy chandelier [. . . ] So without uncomfortable amazement, he stared enchanted at the delicious marvel of awakened life.

The prose is rich, almost overwhelming, and I find myself reading slowly, a chapter at a time. The elaborate visual emphasis, and the precise turns of pharase, call to mind The Secret Service by Wendy Walker ; I wonder if any filiation (direct or indirect) can be traced. The picture of Wylie, above, is a detail of a wild, exotic three quarter length portrait by Cecil Beaton (which I can find only as a thumbnail at the Library of Congress). Beaton’s photographs of Wylie, Sylvia Townsend Warner, and others appeared in the late July 1927 issue of Vogue.

* that is : Giacomo Girolamo Casanova Chevalier de Seingalt (1725-98).

OuLiPo at 50

Pierre Assouline, in the république des livres blog, has an instructive note, “ Ce que l’OuLiPo déjà quinqua génère ”, with an interesting insight about the nature of the writing workshop :

“ un tout petit groupe qui ne se donne pas pour une élite ”

Fr

you monolinguists, that is : “ a

tiny group that makes no claim to be an élite ”.

Recent reading :

— Michael Connelly. The Reversal. A Novel . Little, Brown and Company [2010].

— Sándor Márai. Embers (1942 ; 2001). A novel of vanished worlds, a Hungarian ‘ Leopard ’, beautiful, evocative, and profoundly evasive ; my dire foreboding and thought of The Good Soldier were true in essence, but the central moment of the novel owes more to The Shooting Party . The last half of the book is a monologue that does not quite rise to the level of Marlowe’s narrative stream, and yet is rather astonishing all the same. “ Solitude is very strange too . . . and sometimes as filled with dangers and surprises as a virgin forest. I know all its ways. [. . .] Of course, solitude did not provide me with any answers. Nor, in any complete sense, did books. [. . .] ”

— — — —

The Last Three

From [WW] :

— Jim Steinmeyer. Charles Fort, the Man Who Invented

the Supernatural (a

fascinating byway of American literary history, about our first cross-genre

writer ?)

— P.D.James. Original Sin (murder set in a publishing

house as fallen Eden ; contains a passionate and articulate denunciation

of mainstream publishing treatment of mid-list authors !)

— Bruce Duffy. The World as I Found It (wonderful

historical novel about Wittgenstein, Russell, Moore, Ottoline Morrell,

Vienna.)

After making a passing mention of The Book of Sand in last week’s post, I pulled the book down from the shelf, and noticed that I had only read the beginnings and ends of the book — I had not “ ate every page of it ” — and so I discovered the astonishing tale “ There Are More Things ”, which is Borges’ critical fiction about H. P. Lovecraft ( ! ), a tale that in its concision surpasses the model ; and then re-read the stories I knew, “ Ulrike ” and the two final tales, “ The Disk ”, about a one-sided circle, a perfect object direct from Odin (whose name means “ one ”), and “ The Book of Sand ”, about the “ monstrous ”, infinite book, with no discernible first or last page — he might be describing an e-book — “ a nightmarish object, an obscene thing that affronted and tainted reality itself ”.

One does not usually rank Borges among the prophetic visionaries, but before you dispose of your e-book, consider this :

I thought of fire, but I feared that the burning of an infinite book might likewise prove infinite and suffocate the planet with smoke. Somewhere I recalled reading that the best place to hide a leaf is in a forest. [. . . ] I lost the Book of Sand on one of the basement’s musty shelves.

17 December 10

Current reading :

— Sándor Márai. Embers (1942 ; translated by Carol Brown Janeway from a German translation of the original Hungarian, Die Glut , 1999 ; Vintage paperback, [2001], 15th printing). A beautiful, layered exercise in memory, an evocation of lost Hungarian worlds. The literary terrain is familiar from Davidson’s Eszterhazy stories, but here the atmosphere of doomed nostalgia is unmixed with Davidson’s touches of humor. I am about halfway through, and from page 5 or 6, with a dreadful sense of foreboding, I have been thinking about The Good Soldier . [Gift of EK].

— — — —

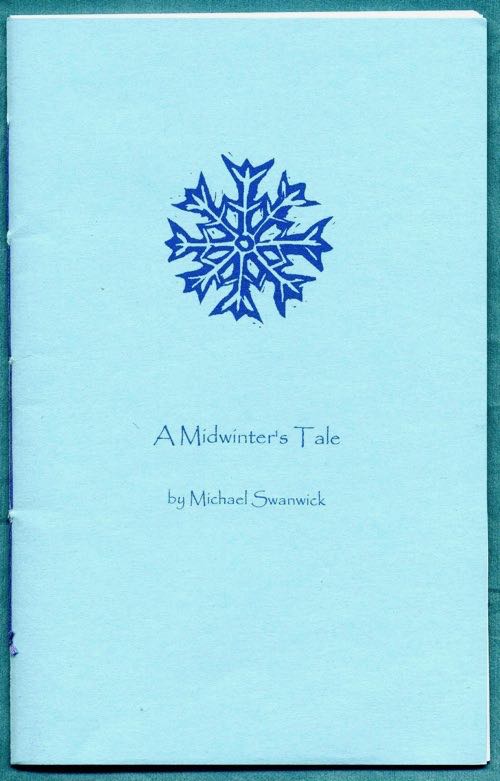

— Michael Swanwick. A Midwinter’s Tale [1988 ; Dragonstairs Press, 2010]. Stitched wrappers with snowflake on upper cover. One of 50 copies, a gift of the author. A delight to have occasion to re-read this wonderful story of first contact, animal people, and humanity in winter.

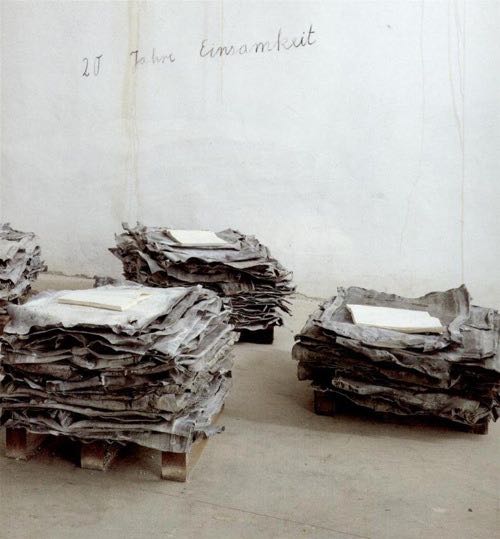

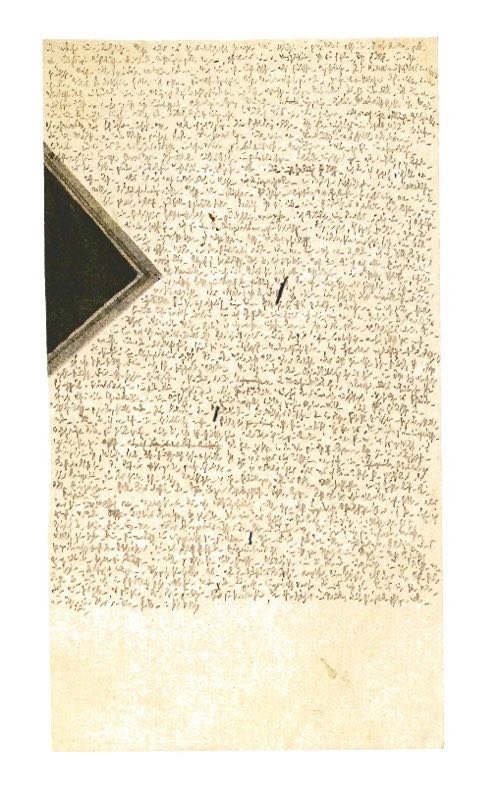

Borges has described The Book of Sand , that Ò monstrous ”, infinite volume he concealed in the Argentinian National Library ; last year the Endless Bookshelf reported on the Snow Books of João Machado ; and now, thanks to the République des Livres blog, your correspondent has learned of the Books of Lead of Anselm Kiefer. The image above is of 20 Jahre Einsamkeit (1998, Twenty Years of Solitude). Pierre Assouline cites in this context a useful sentiment articulated by Francis Bacon, « Puisque je me suis tué à le peindre, pourquoi voulez-vous que je m’acharne maintenant à trouver les mots pour dire la même chose ? » (for which I shall someday endeavor to find the English original).

Your correspondent spent a couple of interesting hours this afternoon cataloguing previously unpublished correspondence of Mervyn Peake, concerning the writing of the first two books of Gormenghast ; now quoted to an appreciative potential buyer.

— — — —

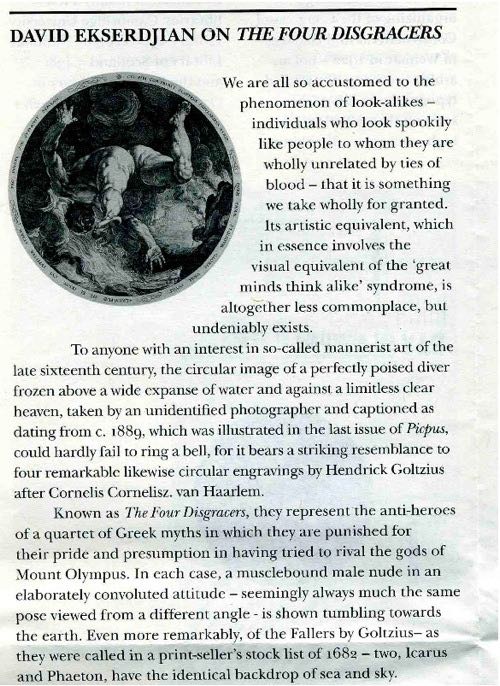

In a recent issue of Picpus , a London literary ’zine of very high standards, your correspondent noticed an essay by David Ekserdjian on the Four Disgracers : Phaeton, Icarus, Tantalus, and Ixion (father of Kentauros).

— — — —

The next update of the Endless Bookshelf will appear on 24 December and will include a short, preliminary discursion on the Magic of Class in fantastical literature. Please continue to send list of the Last Three or other correspondence.

That Time of Year : Best Book of 2010

— Robert Walser. Microscripts . Translated from the German and with an Introduction by Susan Bernofsky. Afterword by Walter Benjamin (New Directions/Christine Burgin, 2010). The most compelling, upsetting, intriguing book of the year, as noted here ; with two close contestants Strange and Wonderful and Hicksville (see below)

four notable books

— William Godwin. [Things as They Are ; or, the

Adventures of] Caleb

Williams , [1794 ; Oxford University Press, Oxford World’s

Classics paperback, 2009]. notice

—

Mary Shelley. The Last Man (1826 ; edited with an

introduction by Hugh J. Luke, Jr., University of Nebraska Press, 1965). notice

—

Stella Benson. Living Alone . Macmillan and Co., [1919 ;

second printing,] 1920. notice

—

Sylvia Townsend Warner. Lolly Willowes or the Loving Huntsman .

Chatto & Windus, 1926. notice

highlights of 2010 : eleven books

— Gregory Feeley. Kentauros . [NHR Books, 2010]. review

—

Dylan Horrocks. Hicksville. A Comic Book . (1998 ;

Drawn and Quarterly Publications, 2010). notice

—

Tony Judt. Ill Fares the Land . Penguin Press, 2010. notice

—

Tom La Farge. Life and Conversation of Animals . Proteotypes,

2010. LIBELLULÆ 1. review

—

Douglas Rushkoff. Program or Be Programmed. Ten Commands for a Digital

Age . [With original line drawings by Leland Purvis.] OR Books,

2010. review

—

Joel Silver. Dr. Rosenbach and Mr. Lilly. Book Collecting in a Golden

Age . Newtown, Pa.: Bird & Bull Press, 2010. review

—

Patti Smith. Just Kids . Ecco, [2010]. brief

notice

— Stories. All-New Tales . Eds. Neil Gaiman and Al

Sarrantonio. William Morrow, 2010. notice

— Strange and Wonderful. An Informal Visual History of Manuscript

Books and Albums . Introduction by Jed Perl. Designed by Fabio Cutro.

Sanctuary Books, 2010. notice

— Peter Straub. A Dark Matter. A Novel . Doubleday,

[2010]. brief notice

—

Mark Valentine. The Mascarons of the Late Empire & Other Studies .

Passport Levant, 2010. review

‘ without a precise reference ’

“ I have unfortunately lost the reference & it is a high crime, I confess, ever to refer to an opinion, without a precise reference. ”

— Charles Darwin, in a letter to Daniel Sharpe, 1 Nov. 1846

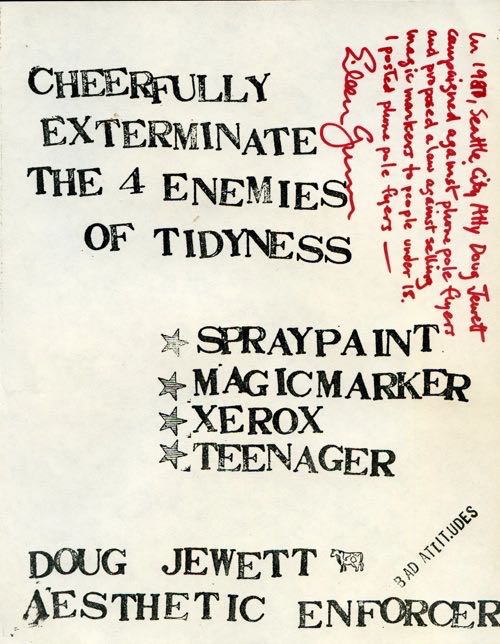

Courtesy of Eileen Gunn and Cory Doctorow, with whose book With a Little Help (2010) these posters are now somehow connected.

7 December 10

Current reading :

— George Orwell. Nineteen Eighty-Four . London: Secker & Warburg 1955 (Fifth printing of the second edition). Re-reading.

— — — —

During the past weekend your correspondence paid a visit to an important literary address ; not, however, the one you might think. The next update to the Endless Bookshelf will look back at the best books experienced during the past year, on 10 December.

The significance of the dust jacket

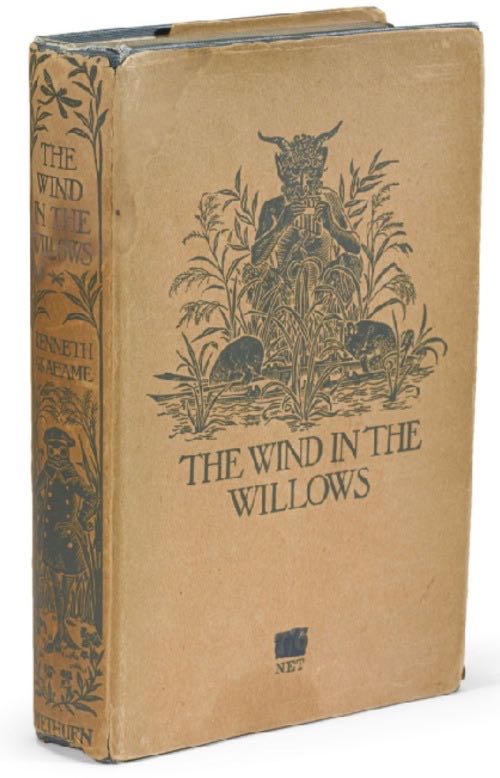

The dust jacket for The Wind in the Willows (1908) presents the gilt stamping of the cover and spine of the book in black on the cover and spine panels, along with the price (6/ in the first issue and 7/6 in the second issue, obliterated in ink here). The contrast between the form of Pan with the syrinx on the front cover and the Toad in motoring gear on the spine is quite remarkable, and yet not the most intriguing aspect. The significance of this dust jacket is that apart from the price it offers no further information whatsoever to the prospective buyer, not a hint as to how the publisher wanted the reader to think of the book, nor even a hint as to how the publisher viewed the book : the flaps and the back panel are blank. This copy, seen in London during recent travels, is up for sale at Sotheby’s next week.

Recent reading :

— Lev Grossman. The Magicians. A Novel (2009 ; Plume paperback, third printing, 2010).

1-2 December 10

Mail Bag :

“ just, you know, more. so often i go there and see only what i saw the

day before, sometimes days before. i suppose you have to eat but i

don’t see why. ” — DS

“ I first encountered your literary musings last year and read the whole lot in one go. I, too, am a fan of ‘ small, odd books ’. Owing to your faithful reporting, books such as Lolly Willowes have found their way to my shelves. A new ‘ comfort read ’, it is, unlike your copy, the G&D first edition in a deco fantasia of a dust jacket. It sits between my great-grandmother’s first of To the Lighthouse and a well-loved copy of Indiscretions of Archie . Summer house shelves should be delightfully eccentric . . . I especially enjoy the posts in which your share why a particular book has meaning for you or how you came to find a particular book.” — EP

“ I enjoy everything on the Endless Bookshelf, but i guess my favorite pieces are the ones that begin by your relating having encountered some book in a special collection or at auction or somewhere in your bookselling travels; you describe the book, with picture of course, and then launch into a strange and illuminating discussion from that place — the Pforzheimer Shelley piece is an example but I know you have done others. In fact, you seem to have invented (?) a cunningly unobtrusive fictional (?) form for an essay. I would be happy to see that vein cultivated further. ” — WW

— — — —

Hard at Work (Temporary Office)

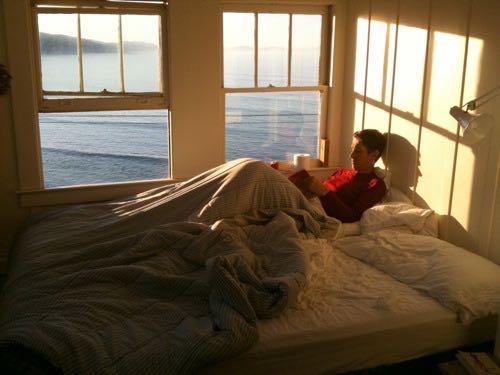

The mail bag also brought a picture of your correspondent hard at work in one of the temporary offices of the Endless Bookshelf :

Reading in Bolinas (portrait by the Anonymous Other)

— — — —

The Last Three

[MV] :

— Two Friends: John Gray & Andre Raffalovich :

essays biographical and critical. Edited by Father Brocard Sewell

(Aylesford, : St. Albert’s Press, 1963). The poet and dandy, later priest, who was “ not

the original of Dorian Gray ”, and his aesthetical friend

and patron.

— Arthur Machen. Things Near and Far (New York :

Knopf,

1923).

The second volume of his autobiography, recounting the time when he seemed

to live in a celestial Zion or in Baghdad-on-Thames, London as an Arabian

Nights city.

— Patrick Leigh Fermor. A Time of Gifts. On foot to Constantinople,

from the Hook of Holland to the Middle Danube (Folio Society,

1999). A journey that started, in its way, in my native Northamptonshire

where

the author was sent as a war evacuee and led a wild childhood in the

country around unknown Dodford.

[DS] :

— Robert A. Heinlein. Starship Troopers . (Poorly plotted, incredibly

didactic, and still compelling.)

— Ursula K. Le Guin. A Wizard of Earthsea .

— Jacques Bonnet. Phantoms on the Bookshelves . (Memoirs of a French

book nut.)

— — — —

Recent reading :

— Driss Chraïbi. L’inspecteur Ali . Denoël [1991 ; Folio paperback, 2007]. Hilarious, layered cross-cultural farce, a novel (in French) charting the life of a Berber author, B. O’Rourke, whose surrealist cop novels (composed in French as dictated by the Arab inspector Ali) are world famous, upon his return to Morocco after long exile, with Scottish wife and foreign born children. Rich and earthy, and I have no idea what connection the author’s account has to the realities of life in that country. This was evidently written at the time of the first Iraq war ; it is the mark of a lofty intellect with direct experience of totalitarianism to make humorous asides about dictators and oppressors in a chronicle of crazed domestic bliss.

‘ gone is the idea of the identical text ’

Yesterday evening your correspondent attended a dinner at the Grolier Club to celebrate the fortieth anniversary exhibition of David R. Godine, Publisher. During the convivial gathering David Godine spoke on the history of publishing and the continuities of printing, design, and personal decision that characterized the five century history of the field. Three things stuck with me from his talk (I simplify and paraphrasehere) : that new technologies tend to reach their fullest potential within the first decades of their emergence (movable type, engraving, lithography, for example) ; that, like the half-tone illustration, the e-book represents a step backwards from the art and function evolved over centuries (it took a hundred years and more for high quality duotones to be achieved) ; and that, with the e-book, the long tradition of textual criticism based upon the idea of the identical text has ended, since with the digital book there is no longer any uniformity of page and font and appearance of the text.

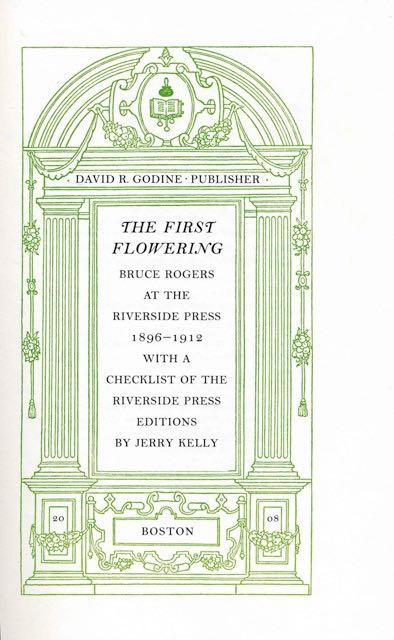

And I conclude with this small token of friendship :

— Jerry Kelly. The First Flowering. Bruce Rogers at the Riverside Press 1896-1912. With a checklist of the Riverside Press Editions . David R. Godine Publisher, 2008 [but 2009]. 54 pp. 36 facsimile illustrations. An interesting little book produced for the Club of Odd Volumes of Boston and such of us who are interested in book design and the history of books. The brief but influential span of Rogers’ work at the Riverside Press is the history of American book design in essence, moving from the heavy influence of the Kelmscott into forms of deceptive simplicity.

Wander in the Archives

The Archives of the Endless Bookshelf have been swept and tidied and a guide has been prepared to assist wanderers. Index would be too strong a term : the headwords tend to be suggestive rather than directive. Start here. Have fun.

This creaking and constantly evolving website of the endless bookshelf : I expect that some entries will be brief, others will take the form of more elaborate essays, and eventually I will become adept at incorporating comments or interactivity. Right now you’ll have to send links to me, dear readers. [HWW]

electronym : wessells

at aol dot com

Copyright © 2007-2011

Henry

Wessells and individual contributors.

Produced by Temporary

Culture, P.O.B. 43072, Upper Montclair, NJ 07043 USA.